The Duluth board of

public works had surveyed the natural boulevard line as early

as 1887, and a newspaper editorial that same year had  made

an appeal to the city council and citizens to develop Duluth's

park systems. Parks had been laid out but they were practically

useless.

made

an appeal to the city council and citizens to develop Duluth's

park systems. Parks had been laid out but they were practically

useless.

When the park board was created two years later, the Minnesota legislature gave it the power to submit bond issues for park development. A $300,000 bond was eventually issued and work on the first leg of the terrace parkway was planned to begin in early 1889.

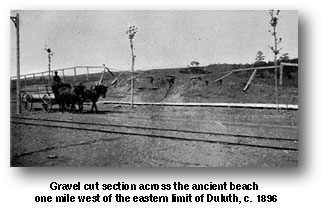

"Work is also to be commenced on the system of parks and the connecting drive-way this spring...It will be over four miles long, and will cost not to exceed $5000. This seems almost incredible, but nature has done the work. It is a natural road bed, graded and graveled by the wash of the Lake, when the subsiding waters reached that level - 474 feet above the present level - only need to have the surface soil scraped off - the drainage attended to and bridges over the ravine. Drives will branch from it off over the uplands beyond, and all the platting into lots outside of this connecting drive, will conform to the surface topography... This is to be a great year for Duluth - the most eventful in its history, I think."

Two work crews--under Rogers's close supervision--began

construction near the top of 10th Avenue East, moving in opposite

directions. By mid-summer three miles of the boulevard were nearly

ready for use.

When the drive was finished two years later, it ran from Chester creek in the east, to Miller's creek in Lincoln Park in the west, rising 450 to 600 feet above lake level, and costing a total of $312,000 (a far cry from Roger's inititial estimates). Wooden fencing was set up along the rim of the new hilltop drive. Granite boulders lined many of the curves such as those around the two little lakes known as Twin Ponds.

During this same time, Leonidas Merritt (of the Iron Range-discovering family) roughed out a three-mile extension westward along the same gravel line from Miller's creek to Oneota, where his family had settled decades before. Rogers made a personal promise that Merritt would be reimbursed from the park board for his efforts.

In 1891, Rogers resigned his position on the

park board and returned to Ohio, where he died two years later.

But his grand park and boulevard plan had been set in motion and

would be carried out by others after him. He was succeeded as

park board president by Luther Mendenhall who came to Duluth in

1868 as an agent of eastern financier Jay Cooke.

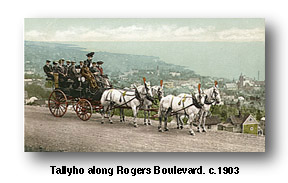

Terrace Parkway proved to be a popular attraction

for both tourists and locals alike. Tallyho or coaching parties--horse

and wagon caravans carrying large groups of sightseers, sometimes

as many thirty wagon loads at a time--were a common sight along

the early highland drive. Travelers were presented with unique

and stunning panoramas of the city and harbor. Presidential candidate,

William Jennings Bryan, while campaigning in Duluth at the turn

of the century, was taken on a tour across the Boulevard and agreed

with the popular opinion that there was no finer drive in America.

The Duluth Daily News claimed it's

only rival in the world was the Corniche Drive along the Mediterranean.

The Duluth Daily News claimed it's

only rival in the world was the Corniche Drive along the Mediterranean.

The park board eventually voted to rename the drive, Rogers Boulevard, in honor of its originator. But despite it's popularity, by century's end it spanned only about five miles.